I have a question that has been bothering me, If this belongs in the current martini thread (Though i do believe it’s a separate topic) i’m happy to relocate.

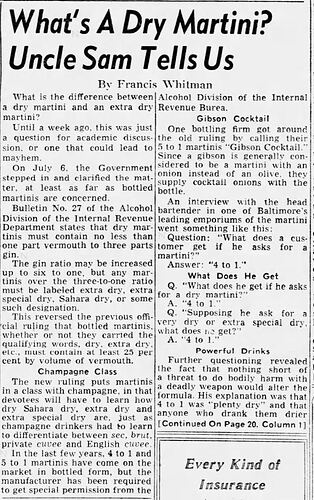

I’ve been spending a lot of time reading and learning about the Martini, I’ve served thousands at this point in my cereer as a working bartender and the variety is endless, but one thing i cant nail down amongst peers is a matter of the prefix “dry and extra dry” and how it pertains to the assembly of the drink.

as i understand it - or at least my interpretation of it - the prefix refers to the the style of vermouth being used, this makes the most sense to me because if i have noilly on hand or dolin dry, and i make a 4:1. that’s a “dry” martini for most people.

personally i like a semi dry martini, 3:1 with a mix of bianco and dry. this is to me a “semi-dry” martini but then when i ask people how they make an extra dry martini, their answer is, 5ml - rinse the serving glass/mixing glass and to me this makes no sense, considering we have brands of vermouth that are labelled “extra dry” and would be perfectly comfortable in a drink at quantities greater than 5 ml and they would still be “extra-dry” martinis.

It seems that to me that the logic doesn’t line up. All things being equal, the “extra-dry” martini doesn’t make sense to be the absence of vermouth rather than the style of vermouth. For all other variations it’s the style over quantity. what do i call a 3:1 with extra dry vermouth, is that dry again?

Some people swear by certain ratios (i’ve been told extra dry is only a rise and everything else is wrong) but this seems foolish to do as martinis are a personal drink that seems to be wonderful in most combinations of volume and style. is this a reaction to most bars not having most types on hand because not enough people order them? it seems to me at least somewhat logical that you would use less of a sweeter “dry vermouth” to emulate the sugar quantity of a extra dry in terms of brix% for the whole drink but it doesnt seem logical to me that the vermouth caps out at 10ml for a 60ml pour of gin in every case of the drink which is another way you might find it built. i’m happy to assume that in the case of most bars, the “extra dry” using less of a regular dry be an emulation of style without being a true “extra dry”.

I cant find any literature that explains this subject in the depth that i need to make a firm decision about how i approach this. how do you make an extra dry martini? why? is there a right or a wrong way? is it by volume or style? please, i need to lay this to rest.