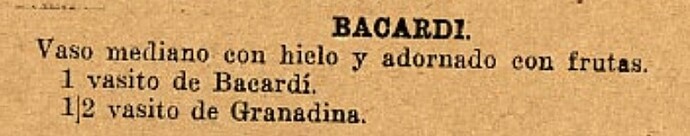

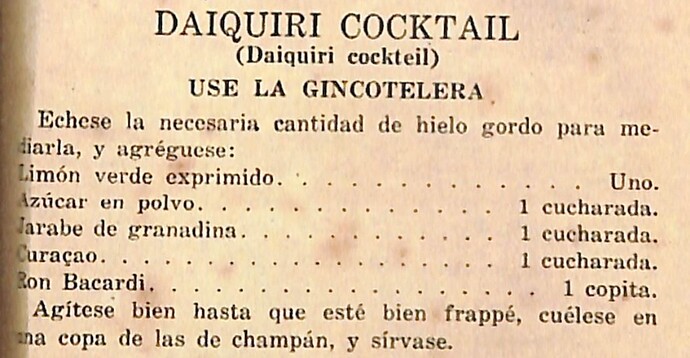

Fortunately we don’t need to rely entirely on that well-worn scrap of paper. In December, 1904 an American Congressional delegation got a quick tour of Santiago and then a banquet at the Hotel Venus. There they got to try the famous Bacardi, according to Joseph Ohl of the Atlanta Constitution, who was on the trip (I must admit that he doesn’t explicitly say it was at the Venus that they tried Bacardi, but that appears to have been the only place they ate and it’s where they stayed, and it was if not the only place in Santiago to get an iced drink in the American style it was the dominant one by a longshot). The Venus, which seems to have been serving some sort of Bacardi-base cocktails since at least 1899 (see the St Louis Post-Dispatch, January 15 1899 p. 33) , was where Jennings Cox and his “siete solteros”–his crew of American and Canadian mining engineers–drank once Santiago fell to the Americans. What Ohl and the Congressmen were served is this:

(Atlanta

Constitution, Dec. 3, 1904, p. 5)

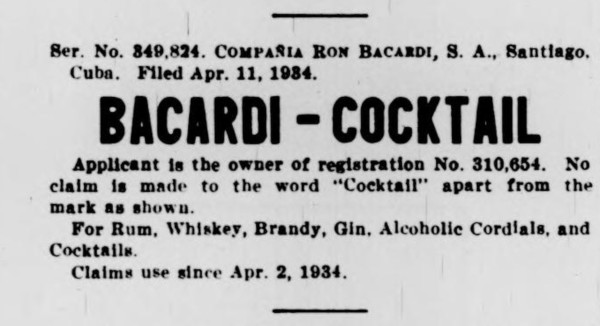

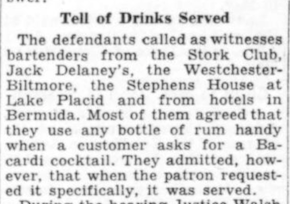

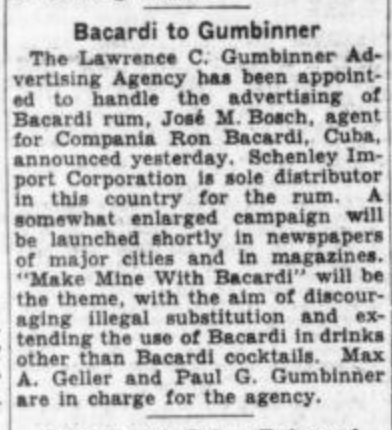

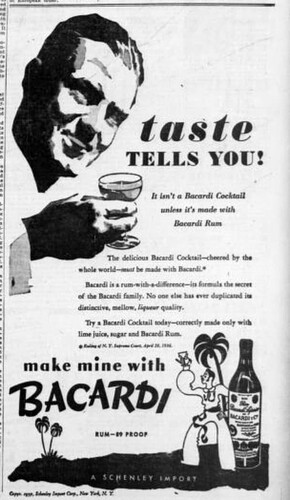

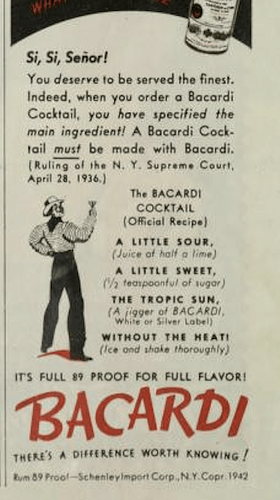

At this point, the name for this simple combination was up for grabs; the Venus bar seems to have called it a Daiquiri, using the name Jennings Cox and his gang gave it. By 1906, however, Bacardi was advertising a “Cocktail Bacardi” (as in this ad from the Panama Star and Herald). If this were anything other than the Bacardi-rum-lime drink that was already floating around one would expect them to provide a little how-to; a little clue as to which particular branch of the cocktail family this drink belonged to. This may be the earliest attempt by Bacardi to get its name on the Daiquiri, but (as BookofMorten shows) it was by far the last. Yet it was a case of too little, too late: if the brand had gone all in with the Bacardi Cocktail, blanketing Santiago and Havana [EDITED TO ADD (where the drink was established as the “Daiquiri” by 1910; see “Alcoholic Explorations,” New York Press, June 12, 1910 p. 8)] with ads and moving more quickly to get American distribution, which didn’t come until 1908, and doing the same thing there, it may have turned out differently.

But the company was uncharacteristically sleepy about the drink, and even once their rum was available in the US at first did nothing to promote their “Bacardi Cocktail.” As late as 1911, it was traveling in at least some parts of America as a “Rum Plush,” a pretty useless name that shows how much the company’s American representatives were asleep at the switch.

As late as 1913, the company’s importers were advertising Bacardi in Rickey form and mixed–inexplicably–with French vermouth, but not mixed into the one drink that it was truly made for. In 1914, that drink finally hit it big, but it was under the name “Daiquiri,” and so it would remain.

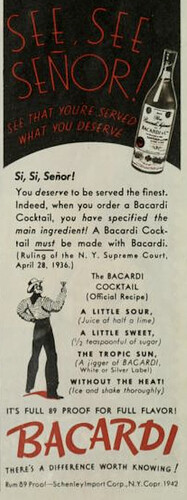

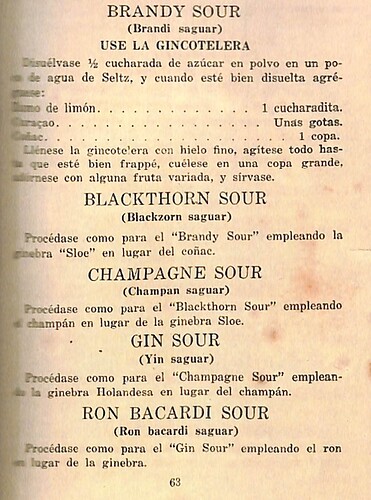

The company didn’t stop trying. In 1930, when Bacardi printed up “Bacardi and Its Many Uses,” a little English recipe booklet to hand out to tourists, it began with the “Bacardi Cocktail,” with Carta Blanca, lime and sugar (the “Bacardi Grenadine Cocktail” cocktail, also with Carta Blanca, was two drinks below). If by then the “Daiquiri” name was too entrenched to dislodge, at least they could try to make sure that a “Bacardi” cocktail had actual Bacardi in it, although their court victory on that count proved to be of little benefit.