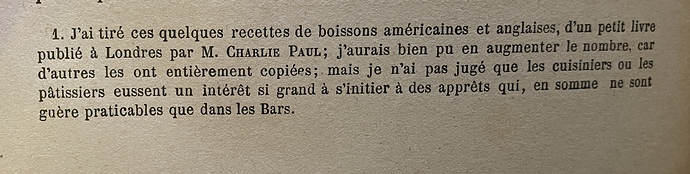

In the Library, we have a copy of a printing (or “edition”) of Recipes of American and Other Iced Drinks that has no publication date in it. This is one that English equipment supplier Farrow & Jackson printed up in the early decades of the 20th Century, quite similar to—yet distinct from—the 1902 edition that Cocktail Kingdom lovingly replicated a few years ago.

An undated specimen is vexing to a librarian, so I recently tried to sort it out. I did not completely succeed, but I did figure a few things out in the process.

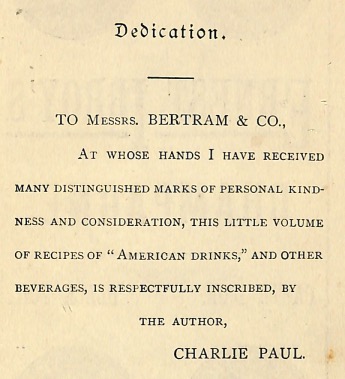

Charlie Paul self-published his first cocktail book in—according to the dedication page—1884, London. (You can check out a PDF of this edition on the EUVS site.)

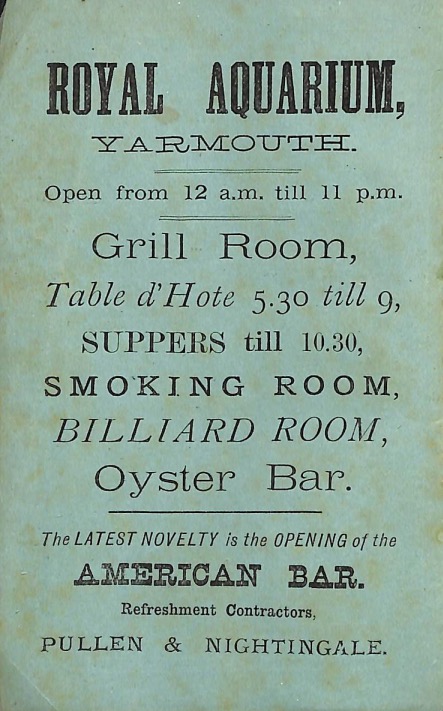

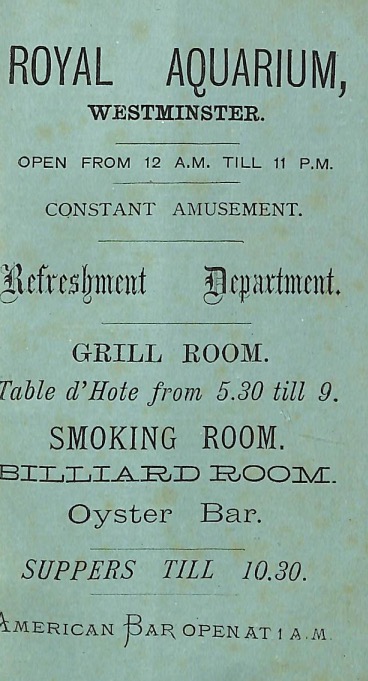

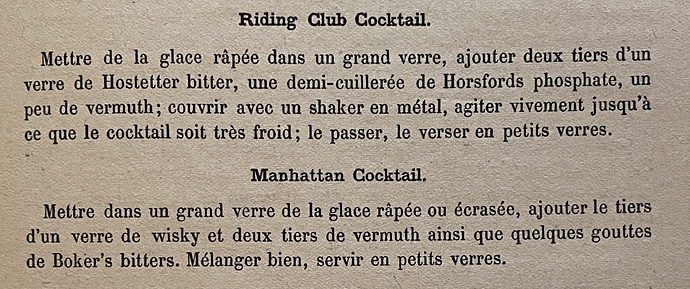

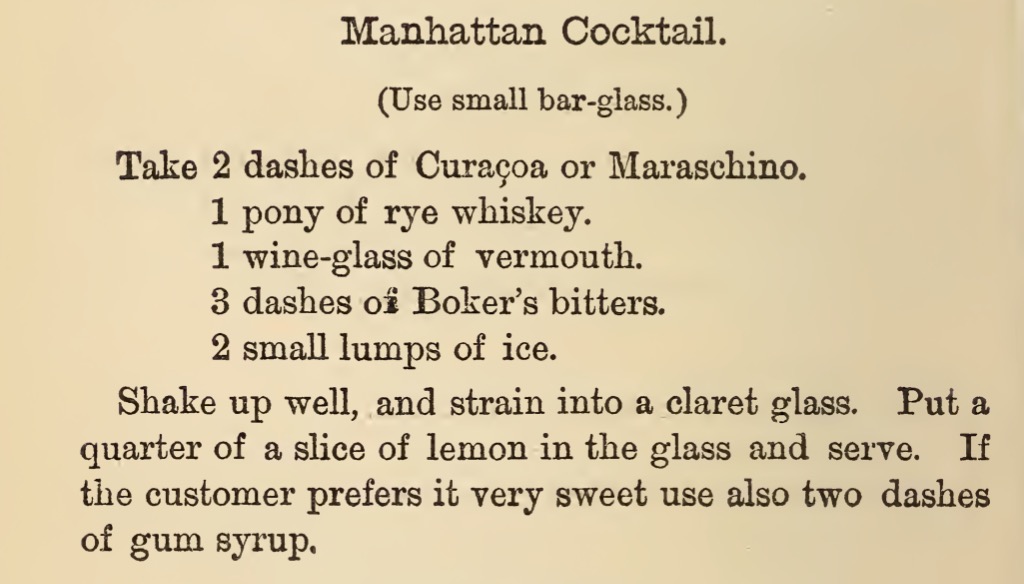

This first work is a brief paperback affair, and quite an interesting one, being a rather early adaptation of American drinks to the London context. It contains originals—including perhaps the first version of the Leave it to Me—and is overall heavy on brandy. The text is up-to-date enough to include a Manhattan recipe, although Paul’s calls for scotch, making it a proto-Rob Roy. (The substitute of scotch may simply be an availability adaptation to 1880s London.) Notably, the volume is decorated with various technical illustrations of bar equipment—a theme that would continue in future editions—although in this self-published edition, the illustrations aren’t in obvious service to any advertiser. In his first book, Paul introduces himself as “of the Aquarium, Late of Paris and New York.” This particular Aquarium seems to refer to an entertainment complex in the seaside town of Yarmouth, which had an American Bar that Charlie Paul presumably worked for, and which is an advertiser in his book. (Photos of the Aquarium at Yarmouth can be seen on Google Images… don’t confuse with the Royal Aquarium in London, a somewhat similar structure.)

In 1887, Paul dramatically updated his book, again self-publishing. The new book is hardcover, and expanded to 78 pages (from 61), and includes recipes for 161 drinks (up from 56).

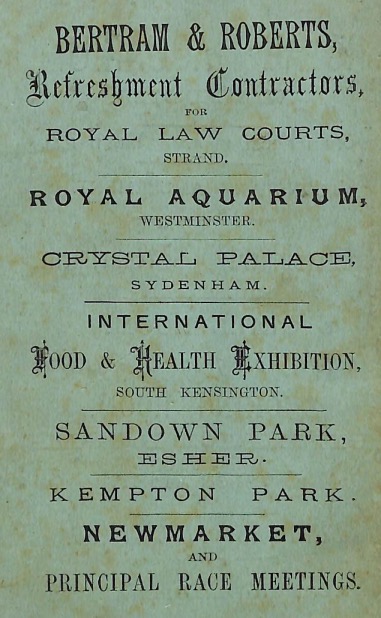

This time, Paul alphabetized the recipes and included a categorical index. Various advertisers underwrote the printing costs, and even more equipment illustrations were included (from the same artists as before). I haven’t done a careful comparison yet, but my glancing impression is that most of the recipe additions are backfill, possibly taken from the Dick & Fitzgerald updates to Jerry Thomas’ book. This time, Paul introduces himself as “of the Aquarium, and the American Exhibition, London, 1887, Late of Paris and New York”. So, Paul was either working the Exhibition (notably headlined by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show) or seeking to capitalize on it.

And as far as I can tell, that was the last edition of his book that Charlie Paul produced. However, fifteen years later, Paul’s unchanged text began to reappear embedded in a series of new editions by the aforementioned Farrow & Jackson. Farrow & Jackson published a lot of copiously illustrated equipment catalogues beginning in the 1880s—you can easily find images on-line—and it seems they seized on Paul’s book as a promotional tool, even though it was a decade or more out of date. Farrow & Jackson used Paul’s text, substituted their own product imagery, and added additional text at the back pertaining to non-alcoholic drinks. F&J issued at least three of their own editions: one in 1902, one in 1915, and the mystery copy we have. There may be more. They all have a different selection of product images, and the pages were re-set for each (no attempt to save money). The only text that sees any substantive changes is the back matter on non-alcoholic drinks, which gets tinkered with quite a bit (and, I presume, had nothing to do with Charlie Paul).

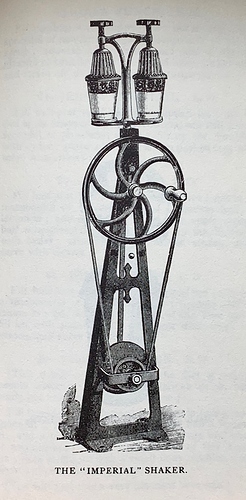

Perhaps the most famous element (today) in the F&J editions is the illustration of their floor-mounted Imperial Shaker product:

This image appears in the 1902 and 1915 editions, but not in our mystery edition. Perhaps the Imperial Shaker was discontinued by that point? Finally, the mystery edition has one other peculiarity: Farrow & Jackson added one single recipe—the Bronx Cocktail—as recipe #162. It’s a run-of-the-mill orange juice version, raising the possibility that F&J was reissuing these books into the 1920s, and somebody felt compelled to finally take a liberty with the 30+ year-old Charlie Paul text.