As promised, a bit of background on this drink, which @Splificator was kind enough to suggest including in the Essential Drinks list.

The interesting thing with Spain is that studying the first years of its love affair with vermouth or studying the birth of its cocktail culture is, essentially, studying the same thing. Both became popular at the same time, in the same venues. Indeed, the first time the Spanish press mentions “la hora del vermouth” (‘the vermouth hour’) as something that happens in Spanish bars, circa 1905, the exact quote is “la hora del vermouth cocktail”.

To understand why cocktails and vermouth were linked, you have to understand that until the late 19th century, the aperitivo as a leisurely practice wasn’t a thing. In the South, they had sherry mid-morning but that was it. But wealthy Spaniards who travelled had fallen in love with Paris boulevard culture – magnificent Art Nouveau cafés serving asbinthe or vermouth on outdoor terraces. And when Madrid, Barcelona and other Spanish big cities got the modern treatment at the turn of the century, some of those wealthy people actually opened cafés, French-style, where they served trendy foreign drinks – absinthe (although it never really took off), vermouth and cocktails too. In that sense, Spain is maybe unique among big European countries in that cocktails didn’t come there from the United States – they came by way of Paris. And for the first few years, American mixed drinks weren’t served in American Bars, they were served and drunk in places called Maxim’s, Maison Dorée, Lion d’Or, their name betraying their inspiration.

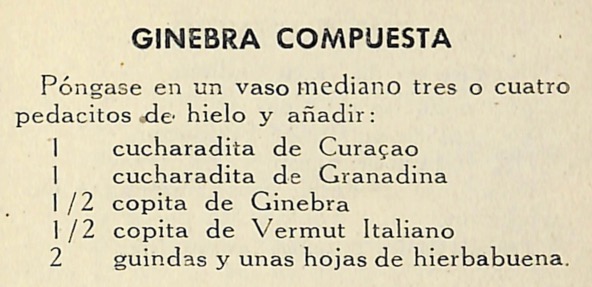

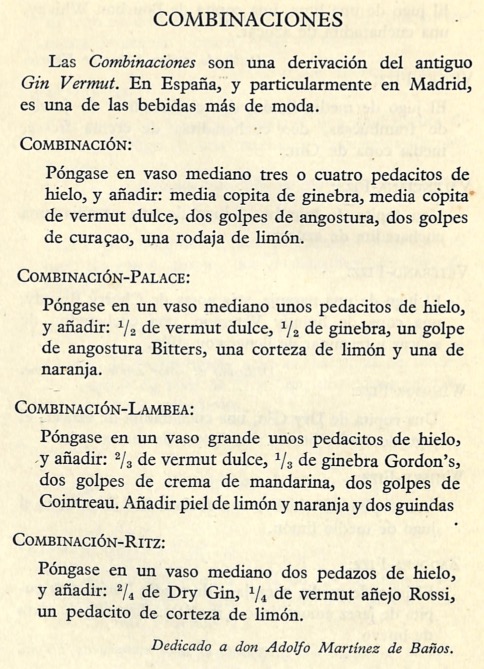

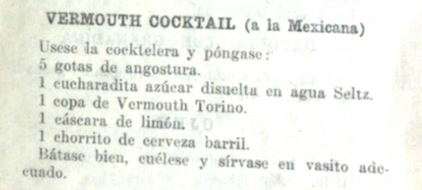

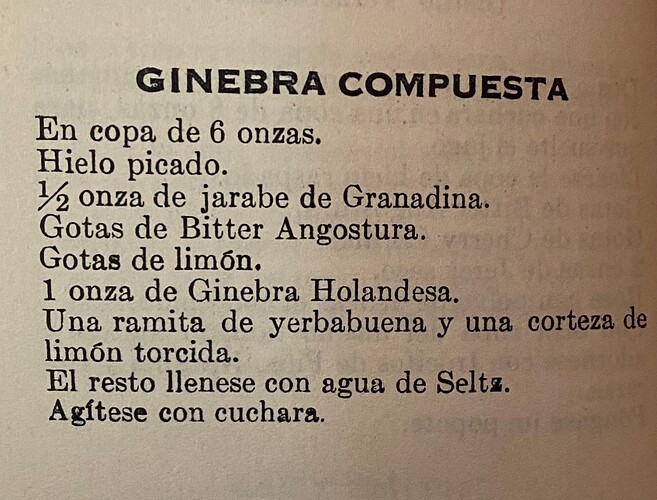

Some of the most popular drinks in those places were vermouth straight, ginebra compuesta (‘mixed gin’) and vermouth cocktail. The last two drinks deserve comment.

The ginebra compuesta was initially a rather traditional gin cocktail (gin, sugar, bitters) or a mixture of gin, sugar, (sometime squeezed) lemon wedge and, maybe, soda. But with such a generic name, it’s no surprise that it soon took the meaning of “a mixed drink with a healthy dose of gin”, and in particular, “gin mixed with vermouth”, as you can see in Martin’s post right above with Sanfeliu’s 1937 recipe.

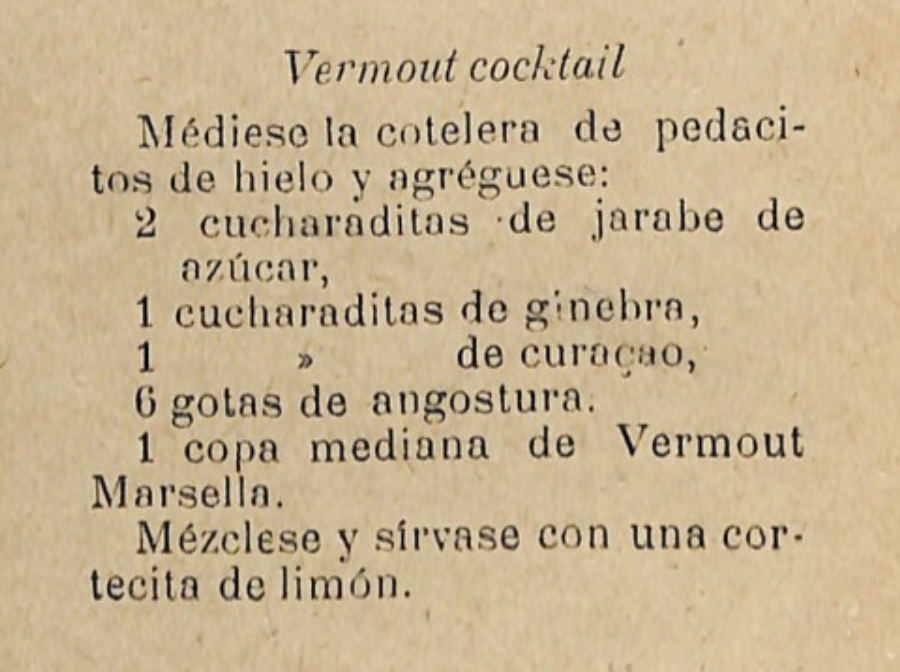

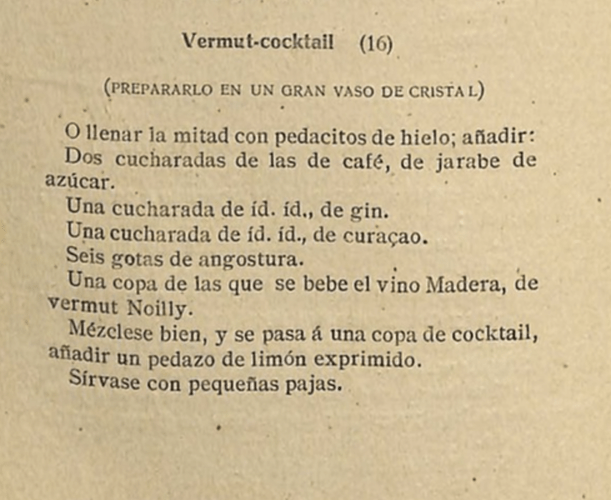

The vermouth cocktail, meanwhile, was not exactly the recipe one finds in Byron or in 1887 Thomas. It followed the template but with a crucial difference: the Spanish version had a spoonful of gin.

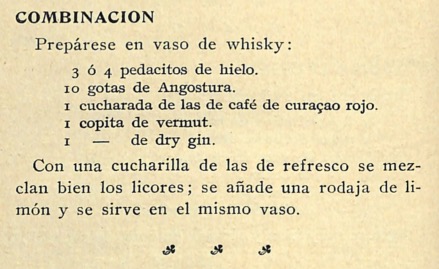

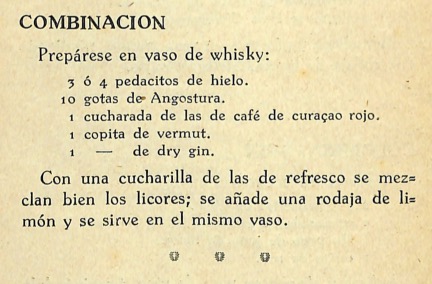

*1905 - Bebidas Americanas, Refrescos y Licores (Ano.)

*1912 - El Arte del Cocktelero Europeo (Ignacio Doménech)

In the Basque country, they pretty much still drink this recipe, which they now call Vermut Preparado and usually make with a healthy splash of Campari instead of aromatic bitters.

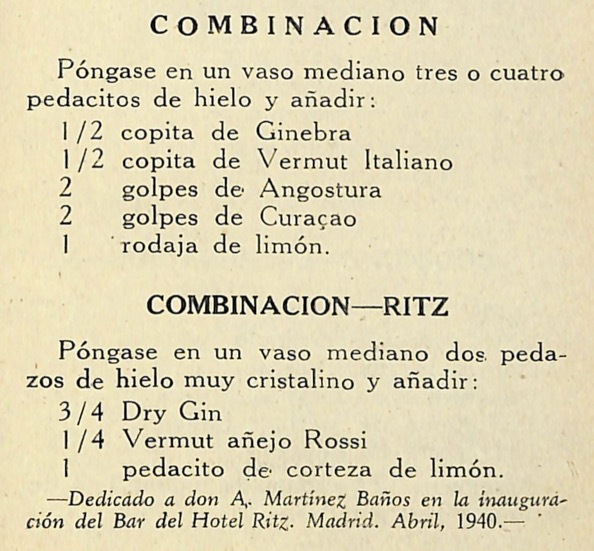

In Madrid, meanwhile, the quantity of gin went up and by the mid-20’s, you’d see Vermouth Cocktail recipes where gin and vermouth share equal billing.

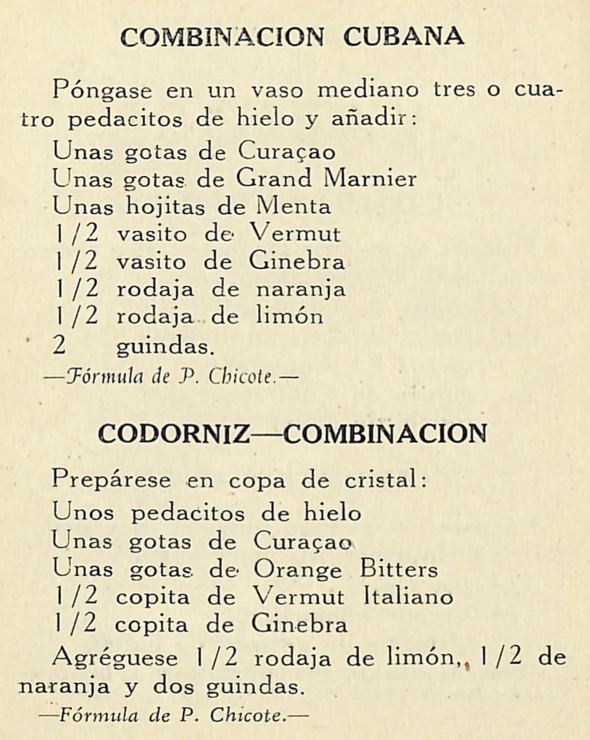

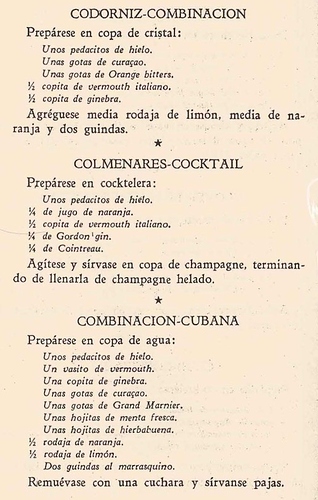

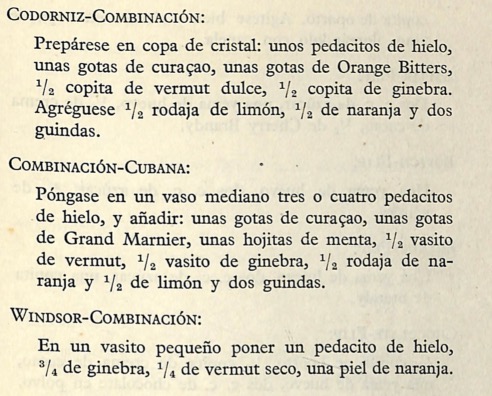

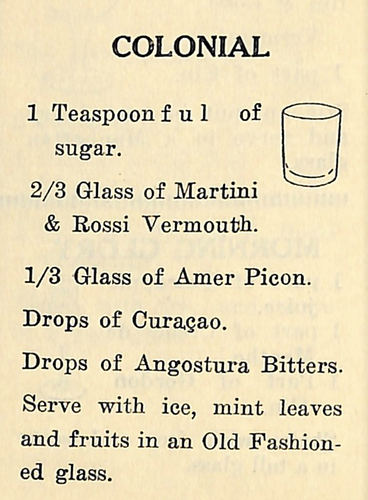

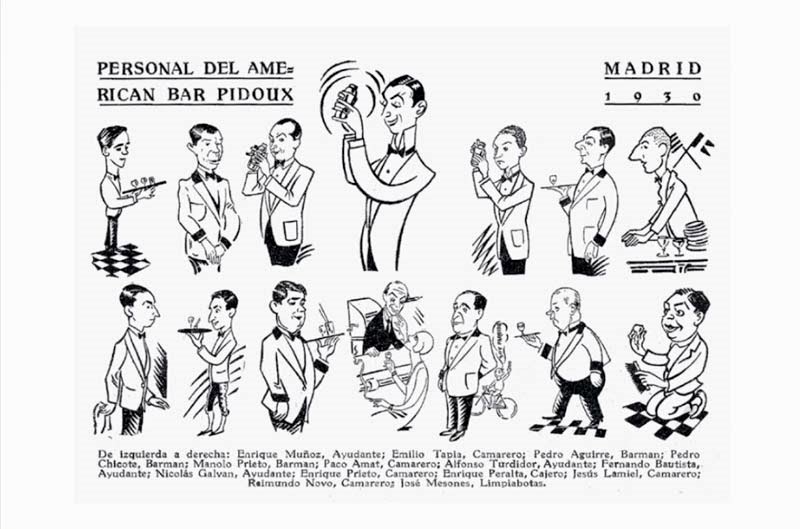

So I always assumed that the Combinacion came from the vermouth cocktail. And that the name came about because the drink’s popularity transcended bars where cocktails were made and, naturally, Spaniards, where they had a choice of vermouth straight up or “combined” with something else, would end up calling the drink just that – a “combination”. It made complete sense. But then I found a text from the early 60’s where barman extraordinaire Pedro Chicote said that the drink actually came “in 1924” from Cuba. I’ve never found trace of that recipe (see the one listed in Martin’s post under 1937 - Sanfeliu) in Cuban books, although the Combinacion, as made at Boadas (who, of course, came to Barcelona from Cuba in the early 20’s) looks like a Colonial + gin.

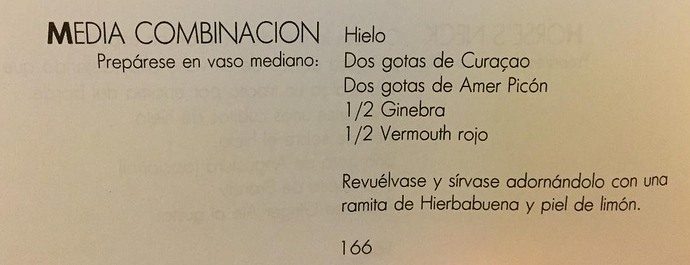

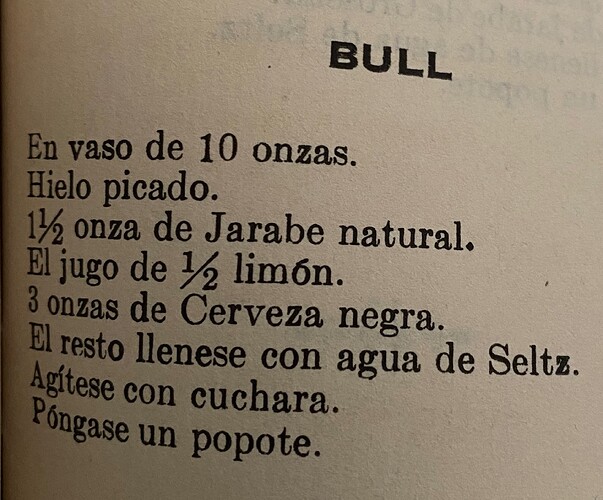

1932 - Sloppy Joe’s

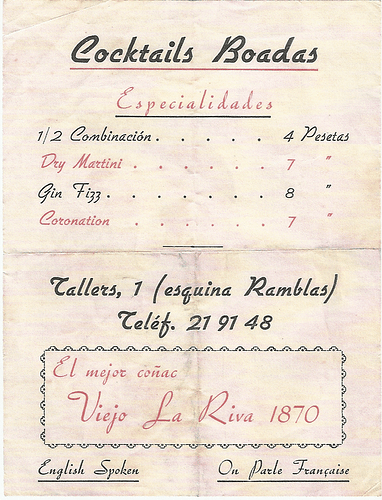

Anyway, by the 1940s, the Combinacion had become the most popular aperitif cocktail in Madrid – Chicote used to name it has one of his bestselling cocktails, with the Dry Martini and the Gin Fizz. The recipes listed Sanfeliu’s 1949 bar tell us all we need to know about the drink’s ubiquity: 6 of them are related to specific bars of the time. The drink remained popular over the next decades before going into decline in the 90s. When I moved to Madrid in 2008, you could still have it in my most places where the bartender was over 40, but only two places actually cared for the drink. One was Del Diego, whose owner had learned his trade with Chicote. There, they made (still do) the “Cuban” version. The other, the temple of the streamlined Spanish combinacion, is the delicatessen on the ground floor of Lhardy, one of the city’s oldest restaurants. It had become a drink for those in the know. You could see it disappear.

I’ve always told Spanish bartenders that they should pay more attention to there own heritage. It’s well and good to follow what’s happening in London or New York but you should also know what people who came before you drank. When I wrote my vermouth book, I made sure to have the Combinacion in there. But the turning point for the drink’s resurgence was two years ago, when Madrid’s leading bartender Diego Cabrera took over an old 1856 taberna. He asked me to help him with the vermouth program and he told me, straight away, that he wanted the Combinacion to take centerstage. I told him to consider the Combinacion as a concept more than an exact recipe – it’s gin, it’s vermouth, maybe something bitter, maybe something sweet. And it’s an essentially Spanish concept – vermouth + gin, in varying proportions, is served all over the country. He decided to reinterpret the Cuban version – which is what @RobertSimonson had at Bar Celona --, to offer the canonical Madrid version and then to create a new Combinacion – with M&R Ambrato, pineapple syrup and orange bitters. The guy turns everything he touches into gold, and now you can find the Combinacion at quite a few more Madrid bars. On top of NYC, the drink can also now be had at Floridita in Havana, where Diego and I had the privilege to give a mini masterclass on the drink’s origin – for me it was a huge pleasure seeing the Combinacion cubana returned to its homeland.

It’s become a bit of a crusade for me and I hope it will become a standard of Spanish bars all over.

At the end of the day, the Combinacion is a very classic, unoriginal drink – we have so many recipes of the style. I think, though, that it proves that cocktails are more than the sum of their parts. The way they’re mixed and served can completely alter the perception of the drink. And then, there’s the cultural context…