Before this comes off as obsessively trivial, three big things happened to American mixed drinks in their history: the first was ice, the second was vermouth, and the third was citrus juice. This concerns the third.

We seem to be pointing at the Crusta as the watershed moment of citrus entering the cocktail, if only in vaguely small amounts. We’ve also got a somewhat elusively-documented earlier tradition of some Americans doctoring their slings and slugs with a little lemon juice (e.g., Sour Whiskey, Whisky Sweet and Sour… see Oxford p. 657). This latter business seems to me the mostly intuitively likely source of the name of the 1850s drink category “Sour”. Punch is always a factor, and the Fix looms large, being quick and small and containing a good amount of citrus juice.

By the 2oth century, we’ve got cocktail-y things under various names (Sour, Daisy) routinely containing the 3/4 oz–1 oz of lemon (or lime) juice that is common in today’s “sour” cocktails.

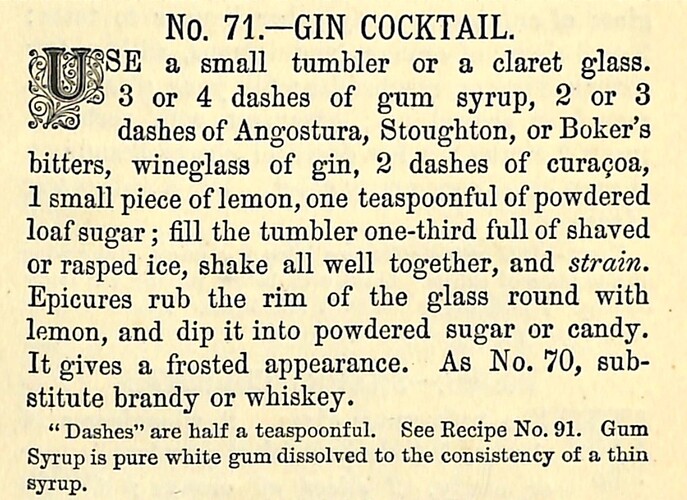

In between the 1850s and ~1910, it’s weird. A lot—but by no means all—recipes in this time period call for quantities of citrus juice that seem neither here nor there, today. I vaguely recall some notion that Golden Era bartender’s were employing dribs and drabs of acid to some sophisticated effect, but… this strikes me as fanciful. Another argument is that “dashes” could be very large, or were wildly discretionary. Today’s mixologists tend to look at recipes from the period that call for 2–3 dashes of lemon juice and instinctively crank that straight up to 3/4 oz or so. While that might result in a drink that is a better suited today’s tastes, when someone like Harry Johnson wrote 2–3 dashes of lemon juice, I’m pretty sure he didn’t mean 3/4 oz.

There’s a pretty well documented spread of sourness in drinks spanning about fifty years that still feels foreign.

- 1/2 lemon is ostensibly 1 oz, but varies

- 1/4 lemon is ostensibly 1/2 oz, but varies, and on average, seems closer to 1/3 oz in my experience

- 4 generous dashes is, at most, 3/4 tsp (~1/8 oz)

Is there an identifiable trend here? A muddle? Was citrus employed habitually sparingly in some situations due to availability/cost? Was it an evolution of taste? Did some people fancy slightly-sour drinks? (Lemonade was common, though.) Some sort of stigma to gradually overcome?

I don’t have answers, but here’s a survey, focusing on the Sour:

Thomas (1862) calls for “a small piece of lemon”, squeezed, for Sours, and “a little lemon juice” for the Crusta

Haney’s (1869) calls for “a portion of the juice of” 1/2 lemon for Sours (and all the juice of 1/2 lemon for fixes)

Simmons (1874) says the Sour is the same as the fix, which he says calls for 1/4 lemon

Thomas (1876) now specifies a 1/4 lemon for Sours

Engel (1881, London) calls for "a small piece of lemon”, squeezed, for Sours [probably just plagiarizing 1862 Thomas]

Johnson (1882) calls for only 2–3 dashes lemon juice for Sours

McDonough’s (1883) explicitly has it both ways for the Sour: you can either use 5–6 dashes lemon juice, OR you use 1/2 lemon

Winter (1884) calls for 3–5 dashes lemon juice across his Sours

Byron (1884) has most Sours calling for 2–5 dashes lemon juice, but a couple—namely the “Continental Sour”—calling for 1/2 lemon

Cordon Bleu (1885) has a Bourbon Sour recipe calling for 1/2 glass (1 oz) lemon juice

Paul (1887) calls for 1/2 lemon for Sours

Thomas (post., 1887) now explicitly calls for 1 dash of lemon juice in the Crusta, with some Sours calling for 2–3 dashes of lemon juice and others for the juice of 1/2 lemon

The ever-surprising Proulx (1888—Chicago) has a whole business on Whiskey Sours, calling for 1/4 lemon or 2 tsp—roughly the same quantity; also discusses the Sour Whisky, which is a Sling with “a little lemon juice”; he also has the Silver Sour and Golden Sour, which are the Silver Fizz and Golden Fizz sans seltzer, with those calling for “the amount of lemon you would for a Whisky Sour”(!)

Schmidt (1891) doesn’t offer a lot of straightforward Sours, but the ones he has call for the juice of a lime, the juice of 1/2 lime, or the juice of 1/2 lemon; his Crusta omits any citrus juice

Boothby (1891, San Francisco) describes (#290) two methods: a Western-style “sour” sling (see also Proulx, above), and an Eastern-style [Brandy] Sour with sugar and the juice of an entire lemon.

Kappeler (1895) calls for 1/4 lemon in his Sours

Herbert Green (1895, Indianapolis) has a couple Sour recipes that variably call for 1/4 lemon or 1/2 lemon

Lawlor (1895, Cincinnati) calls variably for 1/4 lemon or 1/2 lemon in his Sours

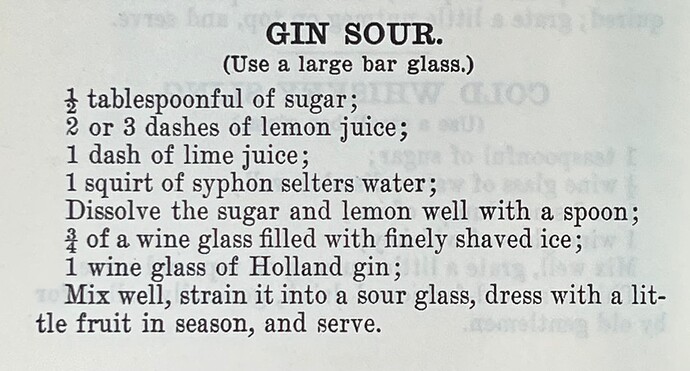

Frank Newman (1900, France) Brandy Sour calls for 1/2 lemon and notes that some prefer no sugar; his Whiskey Sling (#315 & #316) calls for 1/4 lemon(!), his Gin Sour (#133) calls for 3 dashes of lemon juice

Johnson (1900) still calls for drops of lemon juice in the crusta, and 2–4 dashes of lemon juice across his Sours

Mahoney (1905) has sours that call for 2–3 dashes of lemon juice and others than call for 1/2 lemon

Boothby (1908, San Francisco) (#404) has replaced previous with gum syrup or sugar, and the juice of TWO lemons!