I was doing some digging into the history of cocktails in Brooklyn’s bygone grand hotel and came up with a likely connection between the Hotel St. George and Jacques Straub at the Blackstone Hotel in Chicago. Nothing huge, cocktail history-wise, but an interesting footnote.

Very nice work. I have a Hotel St George drinks list from the 1950s somewhere; let me see if I can dig it up.

Here are some more data points on the Brooklyn cocktail, written originally for Edible Brooklyn in 2010 and revised for a book on Brooklyn crafts in 2016; now I’ll have to revise it again.

The Brooklyn Cocktail

By David Wondrich (2010/2016)

Some time around 1880, Manhattan got itself a cocktail. Whiskey, Italian vermouth and bitters, stirred up together. It was the first popular drink with vermouth and America gazed upon it and saw that it was good. Even Brooklyn more or less agreed that it was a fine and useful piece of mixicologizing, despite its bearing the ancestral name of a certain rival city to the west (yes, Brooklyn was its own city then). But Manhattan had a lot of things that Brooklyn didn’t, and after a single, halfhearted attempt at a “Brooklyn Cocktail” by the bartender of the Brooklyn Club (more on that later) Brooklyn seemed to feel no further need to rise up mixing.

Then, in 1901, Curly O’Connor of the Waldorf-Astoria bar—on the present site of the Empire State Building—came up with a “Bronx” cocktail. At first, that fact did nothing to change matters across the East River, or anywhere else. Beginning around 1907, however, for whatever reason O’Connor’s simple, even insipid mixture of gin, vermouth and orange juice began to catch on, and catch on hard. It became the Cosmopolitan of its day, a pleasant, not too strong drink that everybody everywhere—men, women and no doubt forward children, too—could drink. Suddenly, Manhattan and the Bronx, now two of the five boroughs of the same city Brooklyn was in, had an exclusive little club, leaving Brooklyn with the Queenses and Staten Islands of this world. Brooklyn could not sit idly by. Brooklyn had to act.

And, it turns out, act again—and again and again and . . . . The first few Brooklyn Cocktails, you see, did not take. At least the initial attempt, which saw print in Jack’s Manual, a 1908 cocktail guide, was a thoroughly professional effort, combining rye whiskey, sweet vermouth, maraschino liqueur and the delightful French aperitif Amer Picon to excellent effect. A solid B+ in the world of classic cocktails, if not an A-, which easily puts it on a par with the Bronx Cocktail. (The Manhattan, on the other hand, is a straight A+.) Unfortunately, Brooklyn can’t take much credit for it: Jacob Grohusko, the Jack in question, lived in Hoboken and worked in lower Manhattan. At least Victor Baracca, at whose restaurant he worked, was a Brooklynite.

The first inkling the parts of the American general public that didn’t drink in Downtown Manhattan cafes or read cocktail books had that there was such a thing as a Brooklyn Cocktail came in 1910, when another Brooklyn cocktail got a great deal of comment in the nation’s newspapers. Unfortunately, most of that comment was negative.

Whether that’s because its inventor was Wack (literally: his name was Henry Wellington Wack), or because he was a lawyer rather than a bartender, or because he actually lived in Long Beach, not Brooklyn, or finally because his drink was merely a Perfect Martini—gin with splashes of sweet and dry vermouth—with a dollop of raspberry syrup in it, we can’t say. In any case, it did not catch on. The same goes for the next Brooklyn Cocktail, also from 1910. Invented by a Cincinnati German who at least had the good grace to live in the borough, it, too, failed. The fact that it combined absinthe, hard cider and ginger ale could not have helped its fate.

Grohusko’s Brooklyn caught a break in 1914 when Jacques Straub pinched it from Jack’s Manual to include it in Straub’s Manual of Mixed Drinks, which in slightly altered form would go on to become one of the standard works on the subject (Straub did, however, inexplicably switch the sweet vermouth with the dry stuff, thus rendering the drink awkwardly balanced). And yet it still barely registered in the public consciousness. Case in point, Eric Palmer, president of the Brooklyn Press Club, caught by the Brooklyn Eagle in 1916 addressing a waiter: “Bring me a Bronx cocktail. No, make it a Manhattan. I wish they had one named after Kings. Boost Brooklyn.” In those distant days, journalists prided themselves on a detailed knowledge of all of the latest drinks, and if the president of the Brooklyn Press Club didn’t know the Brooklyn Cocktail, nobody did.

Then came Prohibition, and such finer points of mixology became moot. With repeal, though, you would think Grohusko’s drink had a fighting chance: it was included in both the 1930 Savoy Cocktail Book and (Brooklynite) Patrick Gavin Duffy’s 1933 Official Mixer’s Manual, the two books that did more than any others to reset the cocktail clock to the way things were. And yet you never hear of anybody actually drinking the thing, at least not until the current revival of interest in antiquarian formulae. Certainly we can say that its prior claim to the title went unmentioned in December, 1934, when after a long search in response to a reader’s raising the eternal question (“there’s a Manhattan cocktail and a Bronx cocktail, … why not a Brooklyn Cocktail?”) the Brooklyn Eagle’s Art Arthur crowned a concoction by Brad Dewey of Gage & Tollner’s as “THE Brooklyn Cocktail.” The formula? Gin, grapefruit juice and grenadine—or was it Jamaican rum, lime juice and grenadine? The newspaper claimed it was the former, Dewey the latter. In any case, while the dark, woody and convivial Gage & Tollner’s might have been Brooklyn’s oldest and most beloved restaurant, not even that could prevent Dewey’s creation—whatever it was—from falling victim to the same instant public amnesia that greeted its predecessors, to the point that the Eagle itself could wonder, a mere three years later, why there was no Brooklyn cocktail, and trot off in search of one. They found one, naturally. In fact, they found several, for whatever good it did.

In 1945, the Bronx got into the act—not the drink, but the Borough, when James Lyons, its president pointedly wondered in the press why Brooklyn had no drink of its own and suggested what such a drink might contain. Its ingredients: “vinegar as a base; one spoon of raspberries; one-half pony of DDT; one-fourth branch of a tree; one ounce of vodka; one dash Durocher bitters.” This unprovoked attack naturally caused the Borough of Kings to reflect on its liquid representation. Earlier Brooklyns were considered and found wanting. Old-timers were even unearthed in the dusty precincts of the Brooklyn Club who unspooled the tale that the club’s bartender had mixed the first Brooklyn way back in 1883, to commemorate the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge. Unfortunately, said drink was simply a Manhattan with the rye replaced by Jamaican rum, a combination so idiosyncratic that nobody outside the club’s barroom had heretofore heard of it. It simply would not do. So the Borough of Kings pushed its solid men to the fore and set them to mixing. Cocktails were created by the score. Result? Seven years later, the iconic industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes could wonder in the pages of the Eagle why “there [couldn’t] be a Brooklyn cocktail in Dodgertown?” (It would have to be garnished, he thought, “with a razzberry.”)

And so on, world without end. The 1960s and 1970s, of course, had little interest in iced intoxicants. The modern cocktail revival has brought serious mixologists back to Brooklyn, and with them a certain amount of love for the best of the old versions, the one from the Waldorf-Astoria. There are bars in Brooklyn where you can order it and they will make it, and well. The new mixologists have also generated, as is their wont, many a serious attempt at a new Brooklyn Cocktail. And yet, try ordering one of those Brooklyns anywhere but the bar that first made it. Indeed, it seems like the moment anyone with a propensity to mix drinks comes across the Manhattan and the Bronx and no canonical Brooklyn to stand beside them, he or she immediately sets out to fill that gap. But if there’s one thing the story of the Brooklyn Cocktail teaches us it’s that that gap doesn’t want to be filled. Let Manhattan be a cocktail; let the Bronx be another, lesser one, doomed to live perpetually in the shadow of the first. Brooklyn don’t play like that.

Brooklyn Cocktail #1 (1883)

Stir well with ice:

1 ½ oz Smith & Cross Jamaican rum

1 ½ oz Martini & Rossi red vermouth

2 dashes Angostura bitters

Strain into chilled cocktail glass and twist a swatch of thin-cut lemon peel over the top.

Brooklyn Cocktail #2 (1908) –Jack Grohusko’s

Stir well with cracked ice:

1 ½ oz Rittenhouse Bonded rye whiskey

1 ½ oz Martini & Rossi sweet vermouth

½ teaspoon Luxardo maraschino liqueur

½ teaspoon Amer Picon*

Strain into chilled cocktail glass and twist swatch of thin-cut lemon peel over the top.

*This being essentially unavailable in the U.S., substitute ½ teaspoon Amaro CioCiaro and 1 dash Regans orange Bitters No. 6

Brooklyn Cocktail #3 (1910)

Shake vigorously with ice:

1 ½ oz Tanqueray London dry gin

½ oz Noilly prat dry vermouth

½ oz Martini & Rossi sweet vermouth

1 to 1 ½ teaspoons raspberry syrup

Strain into chilled cocktail glass.

Brooklyn Cocktail #4 (1910)

Combine in a tall glass with ice:

2 ½ oz hard cider

1 oz Vieux Pontarlier absinthe

Fill glass with ginger ale and stir.

Brooklyn Cocktail #5 (1914)—Jacques Straub’s

Stir well with cracked ice:

1 ½ oz Rittenhouse Bonded rye whiskey

1 ½ oz Noilly Prat dry vermouth

½ teaspoon Luxardo maraschino liqueur

½ teaspoon Amer Picon*

Strain into chilled cocktail glass and twist swatch of thin-cut lemon peel over the top.

*See Brooklyn Cocktail #2, above.

Brooklyn Cocktail #6 (1934) – Brad Dewey’s

Shake well with ice:

2 oz Smith & Cross Jamaican rum (or Plymouth gin)

1 oz fresh-squeezed lime juice (or white grapefruit juice)

2 teaspoons grenadine or more to taste

Strain into chilled cocktail glass and garnish with maraschino cherry.

Brooklyn Cocktail #7 (1944)—The Hotel New Yorker’s

Shake vigorously with ice:

2 oz Rittenhouse Bonded rye whiskey

scant ½ oz Marie Brizard apricot brandy

½ oz fresh-squeezed lemon juice.

Strain into chilled cocktail glass and garnish with maraschino cherry.

Brooklyn Cocktail #8 (1945)—James Lyons’

"If there is no Brooklyn cocktail, why not conceive one?

Perhaps—

Vinegar as a base.

1 spoonful of raspberries.

½ pony of DDT

¼ branch of a tree

1 ounce of vodka

1 ounce of Durocher bitters.

I do not know how palatable such a Brooklyn cocktail would be, but it would be good enough for the home of ‘Dem Bums.’”

[It might be wise to make a few substitutions and adjust Lyon’s proportions to be more in line with contemporary practice, yielding something like this:

Stir well with ice:

1 spoonful of vinegar-based raspberry shrub*

2 dashes of Fernet-Branca (DDT being banned this will have to do)

2 dashes aged branch extract (or woody old bourbon)

2 oz Industry City No. 2 Vodka

2 dashes Bittermen’s Xocolatl Bitters (Durocher Bitters are, alas, unobtainable)

Strain into chilled cocktail glass and top off with a splash of chilled seltzer.

*Recipes for this abound online.]

Brooklyn Cocktail #9 (1945)—Lynn Gilmore’s

Combine in Old-Fashioned glass:

½ teaspoon superfine sugar

1 teaspoon seltzer

2 dashes Regans’ Orange Bitters No. 6

Add 2 oz Famous Grouse blended Scotch whisky

Add 2 large ice cubes, stir, add a green maraschino cherry and twist a swatch of thin-cut lemon peel over the top.

Would love to see that list!

This sounds like it could be straight off the menu of any number of “NOMA” cocktail bars, today.

Right? I tried my best with it, tongue firmly in cheek, but I think I wasn’t adventurous enough. I did serve it, though, at an event, and it was tasty enough.

As for the St George menu. The good news is I actually have two, from 1948 and 1952. The bad news is that they’re both from the banquet department, and offer a pretty restricted list of drinks, with no Brooklyn among them. I’ll scan the relevant bits ASAP.

I’ve been meaning to ask you, David, if you know where Jacques Straub is buried. I was in Chicago and thought I might pay his grave a visit; I assumed he would be buried there. But I could find no information about a burial site.

I know where he lived (and died) and where the funeral was, but not where he was buried. If I had to guess, assuming he was Christian (which is a pretty safe bet considering he named one of his daughters Christina), I would look at Oak Woods, which is more or less equidistant from his house (which I’m pretty sure still stands) and the church (long gone).

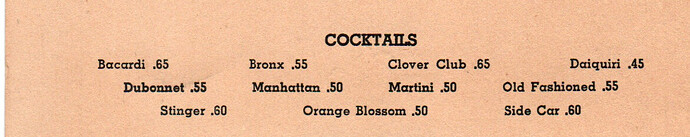

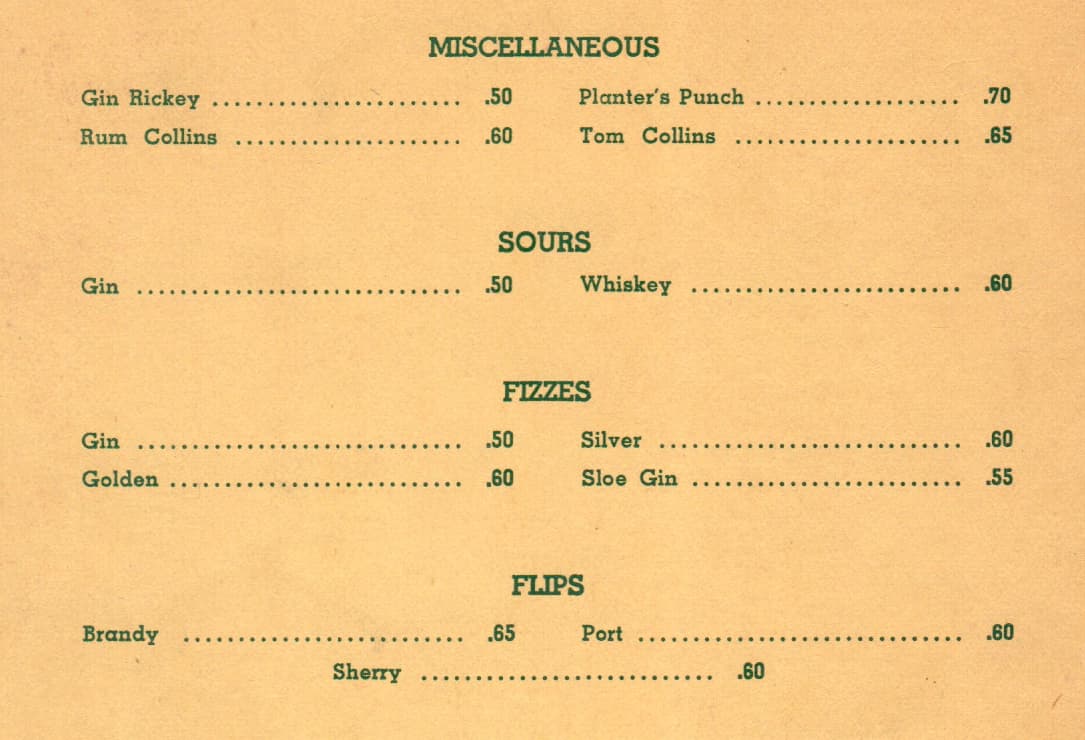

1948 Hotel St George banquet department cocktails:

And other mixed drinks:

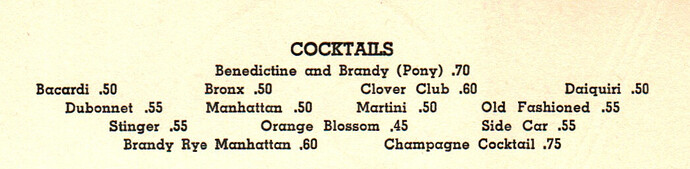

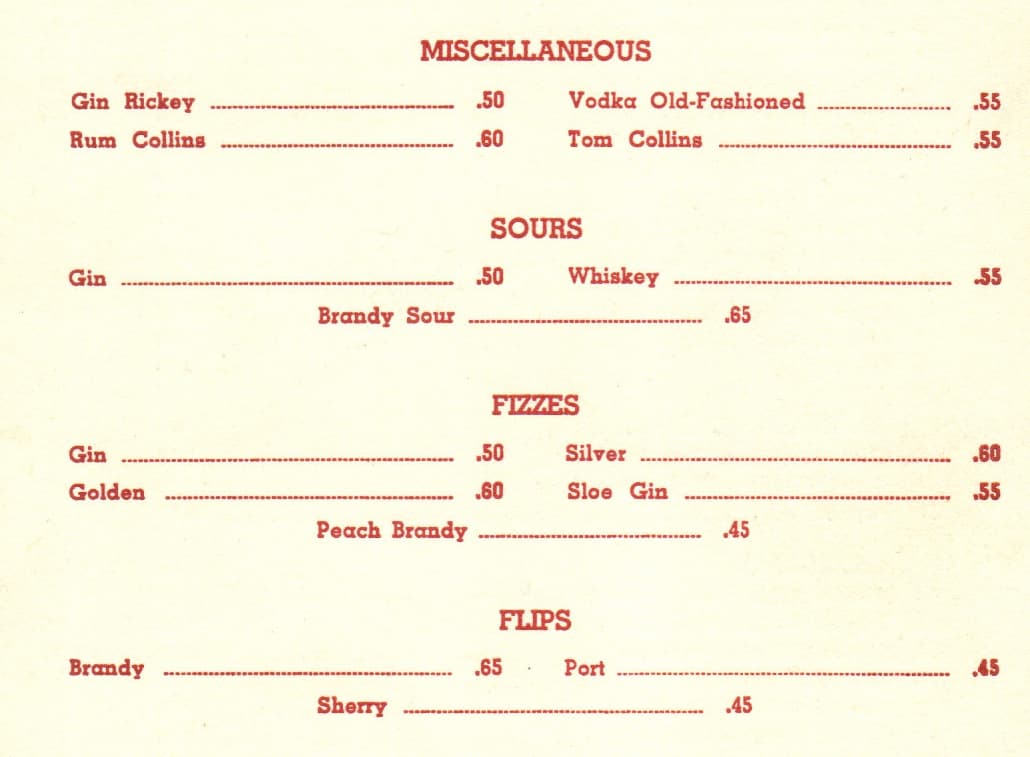

1952 Hotel St George banquet department cocktails:

And other mixed drinks:

That 1952 Brandy Rye Manhattan interests me, seeing as it’s basically the Saratoga Cocktail from the 1887 edition of Jerry Thomas. Also note the 1952 Vodka Old-Fashioned. Even the banquet department felt the winds of change.

It’s funny. Even when I thought I was on to some pretty novel shit back in the day, there was always some old timer who beat me to it. The ‘Vodka Old Fashioned’…geez! I put that on some special menu 15 years ago and caught all kinds of cockeyed looks. Little did I know…

Thanks for all the info guys!